IN MEMORIAM

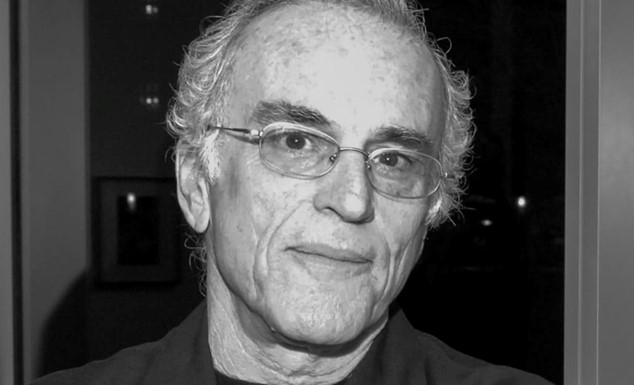

Juan A. Martínez

September 2, 1951 Jaruco, Cuba

October 11, 2020 Miami, Florida

We celebrate the life and prodigious talent of Juan A. Martínez, a pillar of Cuban art studies and his community.

Until the End

I was lucky that I got to know Juan as my professor and mentor and eventually, he became my husband. Through the years, I watched as he collaborated with his colleagues, had meetings and gave feedback to those who sought it, and encouraged the young artists and future art historians. He was generous with his time, a great listener and always helped to promote those who were not given their proper place in the Cuban Art world.

I learned so much from Juan. We visited many museums. It was one of our favorite past times. We would talk about the composition, skill and message of artworks as we made our way through exhibitions. I will miss the happiness that we shared each time we discovered an inspirational piece.

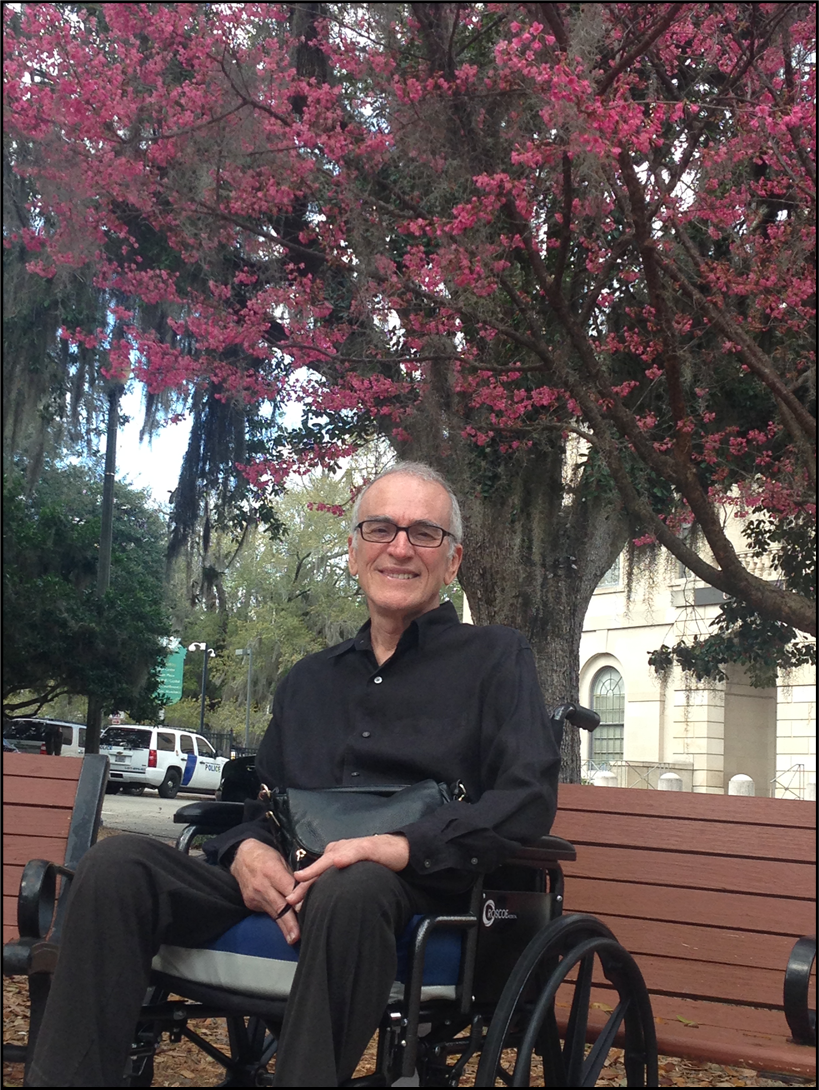

I am amazed at Juan’s perseverance. He met with people and communicated with them, even when he could no longer speak into the computer program that would type out his words. As his voice became a whisper, I would write down what he wanted to say, in a document or in an email. He never gave up. He worked until the very end.

To all of his colleagues who surrounded him with love as the wicked disease ravaged his body, I am so grateful. He had a clear mind to the end and loved working with each of you. Thank you for honoring the bravest man I have ever known and his life’s work.

Ms. Patricia Wiesen

Snapshots with El Profe

Juan Antonio Martínez was born September 2, 1951 in Jaruco, Cuba, to a family of modest means. His family went into exile shortly after the arrival of the 1959 Revolution; first to Spain, and eventually to Miami, where Juan completed high school, continued to college, discovered his vocation for art history and eventually received a PhD from the University of Florida in Gainesville. His dissertation became his first book, the now classic text Cuban Art and National Identity: The Vanguardia Painters, 1927-1950. He spent his teaching career first at Miami Dade Community College, and at Florida International University, retiring from there due to the neuro-muscular disease that ended his life October 11, 2020, at the home of his second wife Patricia Wiesen, in Coconut Grove, Florida. Juan authored the authoritative monograph on Carlos Enríquez (Cernuda Arte Editions), the monograph on Cuban American artist María Brito (A Ver series), and countless catalogue essays and articles. His monograph on painter Fidelio Ponce is forthcoming (Cernuda Arte Editions). Juan is without a doubt, a founding figure in Cuban Art History in the exile, and in the history of Cuban American Art, as contemporary American Art.

I first met Juan in early 1994, when we were part of a national advisory board for the then third reincarnation of the Cuban Museum. Other members were the late Ricardo Viera, Dr. Lynette Bosch and INTAR curator Inverna Lockpez. We spent three intense days together drafting all of the organizing documents for the museum, from Code of Ethics to Collecting and Exhibition policies. Sadly, that third incarnation of the museum went nowhere, but Juan and I became instant friends, and over the years our friendship grew and deepened through collaborations on panels at conferences, museum, and gallery visits, writing projects, always reading each other’s work before it was published, and socializing with family and friends. I thought of him as a mentor, he always reminded me he was merely a slightly older brother. I miss him terribly, but I continue to converse with him through his texts, and since we both are “católicos, apostólicos y Cubanos exiliados,” I know we will see each other again.

Below are three snapshots of our many adventures:

- February 1999, Juan and I were running the first panel exclusively dedicated to Cuban Art at the annual meeting of the College Art Association. And what a gathering of scholars we had on the panel: E. Carmen Ramos, Ingrid Elliott, Rocío Aranda Alvarado, Julia P. Herzberg and Harper Montgomery. The meeting was being held in LA, and it coincided with the opening of the brand-new Getty Museum. Juan and I were like excited school children: we were going to see James Ensor’s The Entry of Christ into Brussels in the Year 1889, which the Getty owned. The two of us ran through the galleries, by passing mannerist works, baroque paintings, some small but exceptionally good Davids and Goyas, some terrific post-impressionist pictures, and then the last gallery dedicated to painting. There was the Ensor in all its splendor. We spent a good 40 minutes in total silence and contemplation. It was extraordinary. As we walked out of the gallery making our way to the public reception for a glass of wine, we said simultaneously: “Neo-figurative Latin American Art owes Ensor a great deal.”

- In the Spring of 2002 Juan and I chaired a panel, on Latin American and Latino art criticism for the Historians of British Art annual meeting in Liverpool, England. A substantial part of the conference was dedicated to Latin America, and we had been invited to present a panel by Francis Frascina and the late David Craven. Unlike CAA panels, the Brits liked less panelists and more depth. We were fortunate to have Florencia Bazzano speak on the criticism of Marta Traba and Holly Barnet-Sanchez speak of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto's rasquachismo and Chicano Art. Juan did the intro, and I did the closing. At the end of the panel, a rather arrogant member of the audience got up and instead of asking a question started ranting about not knowing anything about either of these critics and wondering if they had been worth a panel at the annual meeting. I became enraged at the euro-centric ignorance of the woman, but before I responded, Juan squeezed my knee and leaning into me said: “No te encabrones Alejo. No vale la pena encabronarse por cuestiones de arte y de ignorantes. La vida es breve.” (Don’t get pissed Alejo. It is not worth it to get pissed over art and ignorant people. Life is too brief.) He smiled. I calmed down and responded with humor, brevity, and grace – three qualities I learned from Juan.

- After Ramón and Nercys Cernuda invited me to lecture at their gallery in the summer of 2009 (due in part to Juan’s suggestion), I started visiting Miami more regularly after decades of not setting foot there. Juan would sometimes pick me up at the airport, take me to visit artist’s studios, and after his marriage to Patricia, they would host marvelous lunches at their Coconut Grove home. I would come with my wife Debbi and my daughter Isabel, and Juan would gather Arturo Rodriguez and Demi, as well as María Brito. He would preside over the table like the benevolent patriarch that he was, jokes would be shared, toxic Miami politics discussed, and of course our lives, our loves, always family and art. I owe Juan great and deep friendships with Arturo and Demi, with Ramón and Nercys, with María. He always told me that Miami was his home, and for better or worse, it was the capital of the Cuban exile: “Alejo, its your capital too.”

In November of 2016, now the fourth re-incarnation of the Cuban Museum opened a survey exhibition I organized on the work of Luis Cruz Azaceta. By then Juan was frail and in a wheelchair. He came the day before the exhibition opened and the two of us walked together through the galleries. As usual, his comments were sharp, thoughtful and very generous. Before he left, he congratulated me and said words that I recall to this very day: “These are our artists. They are Cuban and American artists, like us. We have to tell their stories. When I am gone, you are going to be the old man of Cuban art history, and you have to keep telling their stories.” I promised him that I would.

Alejandro Anreus, PhD, Professor of Art History and Latin American Studies, William Paterson University

Abigail McEwen, Alejandro Anreus, Demi and Arturo Rodriguez @ Art Museum of the Americas in DC for the opening of Rafael Soriano: Cabezas (2019)

If it is indeed so hard to say anything of interest about

friendship, then a further insight becomes possible: that, unlike

Love or politics, which are never what they seem to be,

Friendship is what it seems to be. Friendship is transparent.

From a letter by J.M. Coetzee to Paul Auster

El Decano

I first met Juan Martínez around 1986, thru Sheldon Lurie. We were organizing a show of my work in one of the Miami Dade College Galleries, we immediately hit it off, we had a lot of shared tastes in art, music and literature, we were especially fond of the work of Carlos Enríquez and Fidelio Ponce, which we felt at the time were not recognized enough.

Juan was one of my favorite friends, I always called him “El Decano” half in jest and half seriously.

He had an incredible personality, a highly intelligent person without a trace of self-importance or pretentiousness. We got together for lunch every month or so, first he would come to my studio and discuss the work in progress that I was doing, and always in a very constructive way, but he pulled no punches when it came to difficult stages in my work. At the end of every session, we were always hungry, and we went to lunch, but our encounters were always very constructive.

We kept the same relation through the years. When Juan became sick and was unable to move, we communicated by email. Sometimes his caretaker, Marie, brought him to my house in his equipped van, in his wheelchair, and I would show him my latest work. We really enjoyed those moments together.

I do not think I ever met a person with Juan ’s quality of character in facing so many odds. Until the very end, he maintained his habitual composure and great sense of humor.

I will always miss him.

Arturo Rodriguez

Tres Amigos: Arturo, Juan and Alejandro (2018)

Juan Martínez

I first met Juan Martínez casually at an art opening here in Miami in the 1980’s. His cordial and low-key demeanor didn’t begin to reveal the accomplished scholar he was. We continued to run into each other at subsequent openings and developed a good friendship.

Years later I learned that I had been chosen by the A Ver board for a monograph on my work. Needless to say, I was elated by the news and thrilled to hear that Juan had been selected to write the book.

As part of his research, Juan spent weeks in my studio going over hundreds of images of my work. In my mind’s eye, I can see us now sitting at my dining room table sipping café Cubano as we talked about the works depicted in the slides and the creative process that brought them into being.

It was a humbling experience at Books and Books in Coral Gables when Juan talked about the book in front of the large number of people who came to support us.

I will always remember Juan Martínez for his talent, his vast knowledge about art history and for the depth of his friendship.

María Brito

On Juan A. Martínez

I don’t recall exactly how I met Juan Martínez, but neither can I remember not knowing him. I suspect Alejandro Anreus played a role, but only because I have never seen one without seeing the other. They had perfected a repartee that was intellectual and cosmopolitan, both also somewhat combative and always down-to-earth funny – in a word, Cuban. While I grew up in a family that identified as Mexican, I did so in Miami during the 1960s, living in a largely working-class unincorporated community that had quickly became majority Latino. Our neighbors were a unique mix of earlier exiles from the Deep South and newer ones from Cuba. One day in 1968, my sister and I had new playmates living next door, Jorge and Lourdes López, whose family had spent three days on a raft – which apparently also carried their father’s table saw. The day after they moved into the neighborhood, families dropped by to offer the López’s their extra household items. They also hired Mr. López to saw things for them, doing so more as a show of support than urgent need.

In the 1970s, my family moved to Chicago where my new best friends were Puerto Rican and Black, and then everything else, too. By the 1990s, as I started a career as a scholar and teacher, I was fortunate to meet other Cuban-born friends that I somehow had always known, including Carmelita Tropicana, Ela Troyano, and José Esteban Muñoz. I felt at home in their presence.

With Juan and Alejandro, I was also inspired by their bracing engagement with the field of art history, and everything else that came under the rigorous upending of their Cuban choteo. In 2004, I launched the book series A Ver: Revisioning Art History, recruiting both as authors, with Juan writing one of the early books. This series was the first, and perhaps still the only, publishing effort dedicated to monographs on individual artists from the various Latino communities in the U.S.: Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban American, Dominican, and so on. But the idea was to put the focus on the artist’s life and art, and not burden the artist with the task of representing everyone else who shared their ethnicity. Juan got it! He understood that identity and ethnicity were important parts of the story, but one had to start by giving close attention to the particulars of the art and the artist’s life. Not only that, he agreed to write about one of my favorite artists, María Brito.

Juan’s book was more than a purely intellectual exercise, disciplinary maneuver, defense of a political-cum-cultural identity, or “service to the community”—it was an effort to look past the categories these approaches require and to see the artist and her artwork through her own experiences and as an integral part of the world. María herself sets these terms in her autobiographical installation Merely a Player (1993)—commissioned for an exhibition I co-curated—in drawing her title from Shakespeare’s As You Like It:

All the world's a stage,

and all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

and one man in his time plays many parts.

Indeed, as the installation explores, María has played many parts in her lifetime, some written by social convention, cultural heritage, or political circumstance, and others discovered over time, through trial and error, serendipity, and what Juan called her “appropriation of past art and a will to allegory.” María’s art draws upon pre-modern and modern references, from the Baroque to Surrealism, while it also gives unique form to the political ruptures that have been at the center of her own life. María was born in Cuba in 1947, and her parents sent her and her brother to the United States in 1961 through Operation Pedro Pan, the largest exodus of unaccompanied minors in the Americas. In some ways, her art has addressed this rupture, but it has done so outside political and cultural frameworks. Thus, as Juan argued, her work represents “a will to allegory,” but it is an allegory marked by a central paradox: while each component within an artwork has an easily deciphered symbolism, often within an autobiographical register, the larger meaning is ambiguous, offering no easy correlation to social, cultural, political, spiritual, or moral meaning. In her artwork, María constructs fragments of domestic space in a way that engages not only associations with the family and home, but with the unconscious, the nation, and the lasting legacy of the conquest of the Americas. Juan saw this aspect of her work as part of an artistic project to instantiate an “identity in the making,” not a finished product, one wherein the component parts necessarily “exist in tight but uneasy accommodation,” resulting not in absolute truths or counter-truths but in “anxious interiors.” For Juan, these anxious interiors reveal that what is most private about the self is also most public, and most contradictory, making us all “merely players” with at best the opportunity to play many parts, while still remaining a surprise even to ourselves. In summing up an entire book in one paragraph, I run the risk of making Juan seem unbearably dense and theoretical, whereas his writing is eloquent, nuanced, and open-ended with respect to the art and to art history. But also with respect to the artists he studied.

That Juan made a lasting contribution to art history and to generations of students is without question. But what I remember most is his laughter, genial and bracing (in both senses of the word), and filled with the underlying ethics of choteo—of knowing more than those who simply ignore and disdain others, of irreverence because things really do matter in this world, and of a life dedicated to paying close and caring attention where others do not.

Chon A. Noriega, PhD, Director of the UCLA Chicano Studies Center, and editor of the A Ver series of monographs on living Latino artists.

A Mentor and a Friend

The recent loss of Juan Martínez was not unexpected but was deeply saddening to all of those who knew and loved him. Over his years as a professor of art history and specialist in Cuban art, Juan touched the lives of so many people—artists, students, art historians, and curators. I count myself as one of his mentees, despite the fact that I did not attend Florida International University, where he taught for his entire career. From afar, his example and unwavering support allowed me to persevere at a time when there were few role models for being an art historian devoted to Caribbean and Latinx art. Even in the throes of his unfortunate and debilitating illness, he remained committed and curious about Cuban art on the island and the diaspora. I feel fortunate that I can still conjure his joyful voice and infectious smile.

When I arrived at the University of Chicago in mid- 1990s, I was determined to study Dominican art, from the island and its diaspora. While the presence of Dominican artists has improved over the past couple of decades, studies of Dominican and Dominican American art are still rare, a predicament that continues to inform the field’s underrepresentation within studies and surveys of Latin American and Latinx art. To make my way in such a vacuum, I forged bounds with scholars in other disciplines, like the historian Robin Derby, who was then an advanced graduate student in History at the University of Chicago. I built a community of support with my fellow classmates, many of whom had interests outside of the established tracks of Latin American art. Working with this cohort, we invited several scholars to campus to present their work, and they in turn shaped our development.

Juan Martínez was one such scholar. He quickly became a pillar of support over the long haul. As a student, I devoured his Cuban Art and National Identity: The Vanguardia Painters, 1927-1950. This important book, which is a foundational textbook that broadened our collective understanding of modern Cuban art beyond international figures like Wifredo Lam, provided a template for the study of modern art in a Spanish Caribbean nation that was shaped by colonialism, slavery and U.S. imperialism. Juan’s study and continued scholarship paid significant attention to race and class and how these constructs shaped Cuban modern art. Even as my work on Dominican modern art came to articulate the nuances of modern art there, Juan’s study provided a framework from which to start and ask questions. Simultaneously, Juan’s work piqued my interest in Cuban art, which became the subject of my dissertation. Like Juan, I too became fascinated with the interplay of racial and nationalist politics in Cuban art, yet my desire to get to the root of this dynamic drew me to the nineteenth century. In 1999, Juan and my other beloved mentor, Alejandro Anreus, organized the first ever CAA panel devoted to Cuban art. It was a personal milestone for me and other young scholars like Ingrid Elliott and Rocío Aranda-Alvarado, who were also touched by Juan’s scholarship. In the subsequent years, Juan read my dissertation chapters, wrote recommendations, and always welcomed me when I visited Miami, especially after I assumed my job as Curator of Latinx art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. His on-going scholarship, from his work on Carlos Enríquez, María Brito, to his reconsideration of the Miami Generation, continued to open new worlds for me. I miss him deeply and realize that the best way to honor him, is to continue mentoring the next generation the way he supported me. Adios querido Juan. Your life made a huge difference for me.

E. Carmen Ramos, PhD, Deputy Chief Curator of American and Latinx Art, American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

Testimonial/Homage to Juan Martínez

It was a young novice art student who in 1982 walked into Miami-Dade College Wolfson Campus in the heart of downtown Miami and into influential professor Juan Martínez’s art history course. In my first art history course ever, I naturally had no expectations. Entering the class, I saw Professor Martínez instantly; I noticed his unruly mob of jet-black hair, which he did not notice at all. The second reckoning was that I had a teacher of Latino descent for the first time. It was a moment of cognizant awareness, acceptance and questioning why this had never happened in the past.

What I cherish the most from Juan’s art history classes, in those semi-dark light rooms looking at what seemed countless slides, was how accessible he made sharing his knowledge. He accomplished what I now think of as remarkable for someone who came with no previous art history background and little to no experience with Art, other than what I had learned in the K to 12 public school system. He told jokes and shared stories with his students of the lives of these artists and art movements. Prof. Juan Martínez made this foreign and unknown art world seemed accessible and within my reach. I wonder if the familiarity came from hearing the names of Renaissance artists spoken with a Spanish accent or his passion, enthusiasm, and desire to communicate and transfer this information to us, left the same sort of desire to know, create and share, which was also embedded within us. He instilled within me a curiosity and lifelong passion for Art. His evident joy of teaching Art History stayed in my mind and heart. I came away from those courses with a similar kind of burning desire and willingness to know. I left Miami to complete my studies and had many other art history courses. I always sustain an immeasurable amount of respect and appreciation for Juan Martínez and his genuine desire to communicate with passion his love of Art to his students.

In 2016, while participating in the Dialog in Cuban Art, an artist’s exchange project curated by Elizabeth Cerejido, I found myself at the Perez Art Museum in Miami on stage with the distinguished Professor Juan Martínez. The latter moderated one of the panels for the symposium. I felt an incredible sense of honor and accomplishment just being there at that moment in time. Here was Juan Martínez beholding one of the students he taught over thirty years ago, and I was now an esteemed colleague on stage with him. Thank you Juan.

Juana Valdes, Associate Professor of Printmaking, University of Massachusetts

Remembering Juan Martínez

I met Juan Martínez when he applied to a CAA session I was chairing. I had just gotten my Master’s in Art History, and he was already teaching at Florida International University. This was in 1992, one of the first years that CAA presented sessions on modern and contemporary Latin American art. Juan spoke eloquently on “The Experiences and Art of the First Generation of Cuban American Artists in Miami,” which I greatly appreciated as a first-generation Latina myself, but also as an emerging scholar who saw in Juan much hope for the future of our emerging field.

Nowadays it is really hard to understand what it felt to be a student of Latin American art in the 1980s. Back then, it was rare to find anyone teaching or publishing about Latin American art in the United States. Along with few professors like Jacqueline Barnitz and Ramón Favela, Juan Martínez was one of the pioneers in our field. In the 1990s, his wonderful book on the Cuban avant-garde of the 1920s filled me pride and served me as the best ammunition against so many in academia who dismissed the field as lacking anything worth of study. Over the years, I participated with Juan in other projects and events, but it was this first impression of a young, modest, charming, and brilliant scholar that has stayed with me most vividly. He made a remarkable contribution to our field through his numerous publications and his mentorship of so many accomplished colleagues both in the fields of Latin American and Latinx art history.

Florencia Bazzano, PhD, Assistant Curator of Latin American and Latinx Art, Blanton Museum, UT, Austin

A gathering of art historians from South and North America (February 2011, NYC) after the presentation of the María Brito monograph at El Museo del Barrio. (l-r) Florencia Bazzano, Laura Malosetti, Rocio Aranda Alvarado, Yasmin Ramirez, Gustavo Buntinx, Robin Adele Greeley, Andrea Giunta, Megan Sullivan, A. Anreus, Lisa Crossman, and Juan.

Awards

CINTAS Fellowship Lifetime Achievement Award, 2018-2019

12th Annual International Latino Book Award First Place

Triple Crown Award Winner for monograph: María Brito (A Ver), 2010

MacArthur Foundation Grant, 2001

Ford Foundation Travel Grant, 1996

Ford Foundation Travel Grant, 1995

Teaching Incentive Program Award, FIU 1995

Faculty Development Grant, FIU, 1995

Ford Foundation Travel Grant, 1993

Mellon Research Grant, 1992

Samuel H. Kress Foundation Traveling Fellowship, 1990

Florida State University Fellowship, 1986

Florida Endowment for the Humanities, 1982

Cintas Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award with Carol Damian and Jorge Duany, 2018

Books, Chapters, Articles, and Catalogue Essays

Carlos Enríquez 1900-1957: The Painter of Cuban Ballads

Miami Editorial Cernuda Arte, 2010

Maria Brito A Ver: Rethinking Art History monograph series

Los Angeles, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2010 (Peer Reviewed)

A Ver Meeting, UCLA (2005) (l-r) Gilberto Cárdenas, Helvetia Martell, Yasmin Ramirez, Alejandro Anreus, Tere Romo, Maria Gatzambide, Chon Noriega, unidentified, Victor Sorell, Juan, Olga Herrera

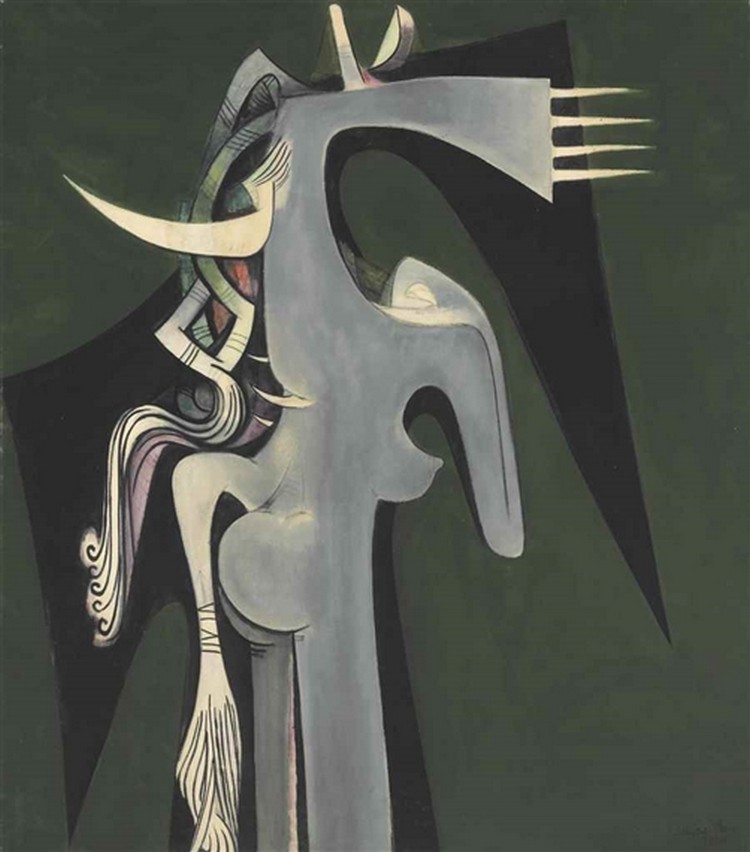

Wifredo Lam in North American Collections: A Look at The Eternal Presence

Miami: Miami Art Museum, 2008: 32-39

Social and Political Commentary in Cuban Modernist Painting of the 1930s

Social Realism in the Western Hemisphere: A Critical Examination of Art Between the Wars

Alejandro Anreus, Diane Linden, and Jonathan Weinberg, eds.

Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006 (Peer Reviewed)

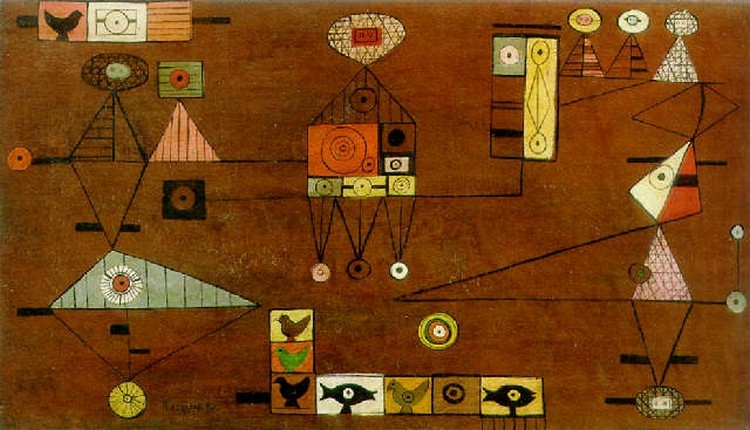

Guido Llinás the Printmaker: An Interview/Essay

Guido Llinás: Forgotten Cuban Master

Bethlehem: Lehigh University Art Galleries, 2003: 17-20

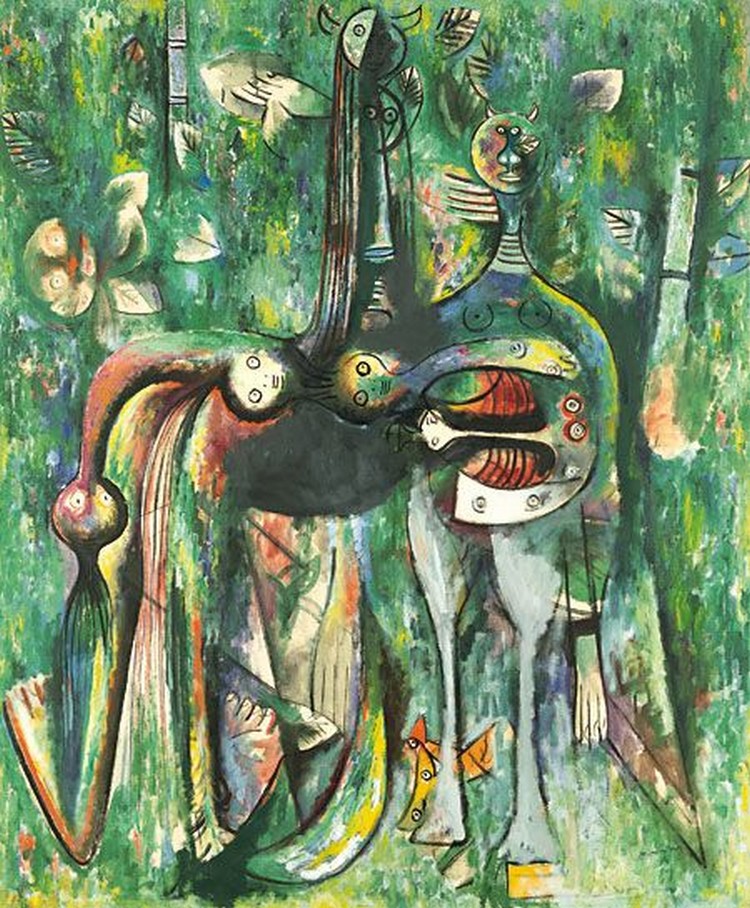

Los Paisajes Míticos de un Pintor Cubano: La Jungla de Wifredo Lam

José Manuel Noceda ed.

Wifredo Lam: La cosecha de un brujo

La Habana: Editorial Letras Cubanas, 2002: 425-37

(Reprint and translation of 1986 article in Caribbean Review)

Cuban Vanguardia Painting in the 1930s

José Veigas, Cristina Vives, et al. Eds.

Memoria: Cuban Art in the Twentieth Century

Los Angeles: California International Arts Foundation, 2002: 52-55.

Modernismo, Criollismo e identidad: el romancero guajiro de Carlos Enríquez (1934- 43)

Estudios 19 (Caracas, enero-julio, 2002):209-226. (Peer Reviewed)

Carlos Enríquez y sus declaraciones artísticas sobre el romancero guajiro

Revista de la Biblioteca Nacional José Martí, 3-4 (La Habana, julio-diciembre, 2000): 24-29.

Lo Blanco-Criollo as lo Cubano: The Symbolization of a Cuban National Identity in Modernist Painting of the 1940s. Damian J. Fernandez and Madeline Cámara eds. Cuba, the Elusive Nation. Interpretations of National Identity. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000: 277-291. (Peer Reviewed)

Cuban Painting in the Republican Period, 1902-1959 Cuba - A History in Art

Daytona Beach: The Museum of Arts and Sciences, 1997

The Invisible Modernism: Early Twentieth Century Latin American Vanguard Art

Art Nexus #24. Bogotá, April-June 1997. (Peer Reviewed)

The Group Los Once and Cuban art in the 1950s: Guido Llinás and Los Once After Cuba

The Art Museum at Florida International University, 1997

Una introducción a la pintura cubana moderna, 1927-1950

Cuba: Siglo XX, Modernidad y Sincretismo

Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, 1996. (Peer Reviewed)

Antonia Eiriz in Retrospect

Fort Lauderdale Museum of Art, 1995

Some Observations on Arturo Rodríguez's Life and Paintings

Fort Lauderdale Museum of Art, 1994

Cuban Art and National Identity: The Vanguardia Painters, 1927-50.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1994. (Peer Reviewed)

Cuban Vanguard Painting in the 1930s

Latin American Art #2 (Arizona: Spring 1993): 36-39. (Peer Reviewed)

A Preliminary Study of Agustín Fernández' Formative Phase

Agustín Fernández: A Retrospective

The Art Museum at Florida International University, 1992

Afrocubans and National Identity, Modern Cuban Painting: 1920s-1940s

Athanor XI. Florida State University, FL 1992: 70-75 (Peer Reviewed)

Modernism, Tradition, and Nationalism: Carlos Enríquez' 'El Rapto de las Mulatas’

Caribbean Studies. 1-2 (San Juan PR: Summer 1989): 101-111. (Peer Reviewed)

The Mythical Landscapes of a Cuban Painter: Wifredo Lam's 'La Jungla'

Caribbean Review #2 Florida International University, 1986: 32-36 (Peer Reviewed)

Years of Friendship. (l-r-top) Annette Bosch-Pizzi, Charles Burroughs, Juan, Lynette Bosch, María Brito. (l-r-bottom) Mario Bencomo, Demi and Arturo Rodriguez

Exhibitions and Book Reviews

Andrea O’Reilly Herrera. Cuban Artists Across the Diaspora, Latino Studies (January 2012)

Alejandro Anreus. Orozco in Gringoland. Art Journal (Spring 2003 issue)

Lynette M.F. Bosch. Ernesto Barreda, 1946-1996. Art Nexus No. 23, January-March, 1997

Edward Lucie-Smith. Latin American Art and Marta Traba. Art of Latin America 1900- 1980 Hispanic-American Historical Review, Vol. 76, No. 2, May 1996

Luis Camnitzer. New Art of Cuba. Art Nexus No. 14, October-December 1994

The Studio Museum in Harlem. Wifredo Lam and his Contemporaries 1938-1952. Art Nexus. No. 57, January-March 1994

Selected Papers Presented in Professional Conferences

and Invited Lectures

Wifredo Lam, entre el Caribe y Europa

Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey

Monterrey, Mexico, October 30, 2008

Cuban Art in Miami since 2000 Cuban Art Today Symposium

University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, April 10, 2008.

The Artistic Vanguard in Cuba, 1920s-1940s Cuba: Art and History from 1868 to Today

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montreal, Canada, April 2, 2008

Beyond Picasso and Afro-Cuban Culture: Wifredo Lam’s The Eternal Presence, 1944

Wifredo Lam in North America

Miami Art Museum, Florida, February 10, 2008

Maria Brito’s Symbolic Interiors and the Cuban-American Experience

Siglo XXI, Latino Research into the 21st Century

University of Texas at Austin, TX. January 27-30, 2005 (Peer Reviewed)

Primitivism from Within, Aspects of the Life and Work of Wifredo Lam and Carlos Enríquez

Conference on Caribbean Visual Culture

Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, New York University

New York, April 24-25, 2003 (Peer Reviewed)

La representación de una cultura blanco-criolla en la pintura moderna cubana de la década del 1940

Centenario del Natalicio de Wifredo Lam (a conference on the occasion of Lam’s centennial birthday)

Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam, La Habana, Cuba. December 10, 2002 (Peer Reviewed)

Afrocubanismo, Criollismo, Barroquismo y Lo Cubano en la pintura del período republicano

Latin American Studies Association, XXIII International Congress, Washington D.C.,

September 7, 2001 (Peer Reviewed)

Cuban Colonial and Republican Art: Thematic Continuities

Cuban Collection, Museum of Arts and Sciences, Daytona Beach, Florida, May 1, 2001

Contemporary Cuban Art, A Synthesis of the National and the International.

Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania, March 15, 2001

From Modern to Contemporary: Cuban and Cuban American Art

from the Lowe’s Permanent Collection

Lowe Art Museum, Coral Gables, Florida, February 1, 2001

From the Good Neighbor Policy to the Trade with the Enemy Act:

Cuban Art Exhibitions in the United States, 1939-1995

Austin Museum of Art, Austin, Texas, September 24, 1999

Imagining the Nation: Cuban Painting in the Republican Period, 1902-1958

Institute of Latin American Studies, University College London, London, UK. November 27, 1998

La Pintura Moderna en Cuba, la Escuela de París y la Expresión de lo Cubano

Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain. April 16, 1996

The Invisible Modernism: Early 20th Century Latin American Vanguard Art

Southeastern College Art Conference, Washington D.C., October 13, 1995 (Peer Reviewed)

The African Presence in Cuban Art, 1920-1995

University of Florida, Gainesville, FL. March 17, 1995

Memory and National Identity in Cuban Art

Norton Gallery of Art, West Palm Beach, FL. October 23, 1994

The African Presence in Contemporary Cuban Art, 1945-1993

Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI. April 22, 1994

Afrocubanismo and its History.

Panelist, Brandeis University, Boston, April 20, 1994

Examining the African Presence in Cuban Art and Society

Panelist, Nexus Contemporary Art Center, Atlanta, GA. February 25, 1994

The Art and Experiences of the First Generation of Cuban-American Artists

Panelist, The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY. November 8, 1993

Latin American Art and Its Impact on Contemporary Art

Panelist, The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY. January 23, 1993

Fidelio Ponce and His Times

The Cuban Museum of Art and Culture, Miami, FL. November 20, 1992

The Representation of the Peasant as a Metaphor for the Nation: Cuban Painting 1930s

Latin American Studies Association, XV International Congress, Los Angeles, CA. September 25, 1992

(Peer Reviewed)

The Art and Experiences of the First-Generation of Cuban-American Artists in Miami

College Art Association, 80th Annual Conference, Chicago, IL. February 12-15, 1992.

The Art of Juan González: 1975-1990

Center for the Fine Arts, Miami, FL. February 6, 1992.

The Afro-Cuban Presence in Cuban Art, 1850-1950

International Congress of Americanists, New Orleans, LA. July 7-11, 1991. (Peer Reviewed)

Other Conference Related Activities

Wifredo Lam in North America: A Symposium

Moderator, Miami Art Museum, Miami, FL. May 17, 2008

Women in Cuban Art: The Artist and the Image

Chair/Discussant. 6th CRI Conference on Cuban and Cuban-American Studies Florida International

University, Miami, FL. February 6-7, 2006 (Peer Reviewed)

Latin American Art: The Critical Discourse from Within

Co-chair with Dr. Alejandro Anreus

28th Annual Conference of the Association of British Art Historians, Liverpool, UK. April 5-7, 2002

(Peer Reviewed)

Points of Contact Between Cuban and US Art

Chair, 4th CRI Conference on Cuban and Cuban-American Studies

Florida International University, Miami, FL. March 6-9. 2002 (Peer Reviewed)

Cuban Art: Encounters, Divergences, Transculturation, and Crossovers

Chair, College Art Association 87th Annual Conference, Los Angeles, CA. February 10-13, 1999

(Peer Reviewed)

Contemporary Cuban Art: from Modernism to Post-Modernism

Chair, 1st CRI Conference on Cuban and Cuban-American Studies.

Florida International University, Miami, FL. October 10, 1997 (Peer Reviewed)

The Teacher

My favorite part of working at FIU was the students. Teaching at FIU confirmed my love for sharing with students my knowledge of art history. The challenge was to make it relevant to their lives for majors and non-majors alike. In general, teaching there gave me a lot of positive energy, satisfaction, and many good memories.

* * *

He became the expert on Cuban art of the Vanguardia period. He represents FIU in a level of scholarship that is respected throughout the academic community. That’s a very lasting legacy.

Carol Damian, PhD

Florida International University

University Park, Art and Art History Department, Miami, FL

Professor Emeritus, 2013

Chair 2006-2011

Professor 2005

Associate Professor 1996

Assistant Professor 1990

Subjects: Modern Art, Contemporary Art, Art and Politics, History of Cuban Art, Methodology, and Special Topics in 20th Century Art.

Miami-Dade Community College

Wolfson Campus, Arts Department, Miami, FL

Associate Professor 1984-89

Assistant Professor 1981-84

Instructor 1978-81

Subjects: Art History Survey I and II, Modern Art, and Interdisciplinary Humanities.

Curatorship

From Modern to Contemporary, A Selection of Cuban and Cuban-American Art from the Lowe’s Collection. Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, November 15, 2000

Origins of Modern Cuban Painting

Frances Wolfson Art Gallery, Miami-Dade Community College

Miami, Florida,October 12, 1982

FIU Top Scholar Award, Professor Emeritus (2013)

Editorial Board

Cuban Studies, a scholarly journal with rotating editorship. Edited by the Department of History of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Member of editorial board.

(Courtesy of the Estate of Juan A. Martínez)

Notes on Collecting Modern Cuban Art in Miami, 1980-2010

Juan A. Martínez, 2018

Today, there are a number of magnificent private art collections in Miami. The best known are those placed in public display by their owners, namely the Margulies Collection at the Warehouse, the De la Cruz Collection, and the Rubell Family Collection. The Jorge Perez collection is also well known because he donated a large part of it to the Dade-County museum that bears his name. These, however, are the tip of the proverbial iceberg. Most are of contemporary art, yet other periods of art and non-western art are well represented in South Florida private collections. The practice has been steadily growing since the 1980s and given extra impetus by the presence of Art Basel and its satellites post-2001.

When the wealth of art collecting in Miami is documented and the story told, I am sure that modern Cuban art (1920s-1950s) will fill one long chapter. What follows is a personal testimony of the collection of such art in this city since 1980. By the use of the names Miami and this city, I often mean Dade-County. The observations are from an art historian, who has studied this art with an eye in archives/libraries and another in the artworks. The collections, which have grown exponentially in the last thirty years, offer today a wealth of visual documentation to curators, critics, and scholars producing exhibitions, catalogues, books, and videos on this period of Cuban art. All along my writings and lectures have benefited considerably from being exposed to Cuban art in Miami. My aim is art historical documentation using facts, descriptions, and anecdotal evidence. The time-line is 1980 to 2010, when I first and last curated an exhibition of this period in Cuban art.

This narrative depends on knowledge based on forty years of conversations with collectors, visits to collections, galleries, and museums, as well as research on the art itself. My memory of the art in specific collections is aided by recently reviews of exhibition catalogues, Sotheby’s and Christie’s sales catalogues, newspaper articles, and informal interviews with gallery owners. The story gives a brief introduction to modern Cuban art and to the collectors, outlines collecting issues, gives an account of the arrival and circulation of the art in question, and offers an insight into specific collections. Descriptions of the artwork in the selected collections is meant to give a sense, if highly concise, of the art itself and aspects of its importance in relation to the artist’s career and/or Cuban art.

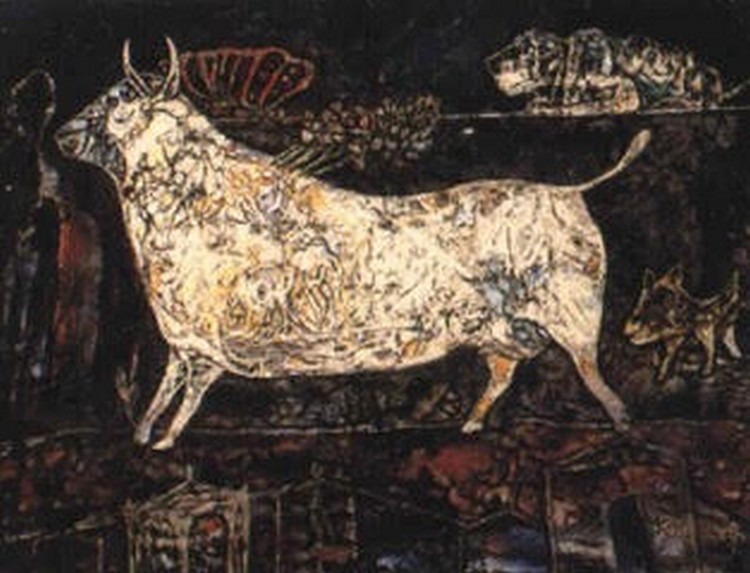

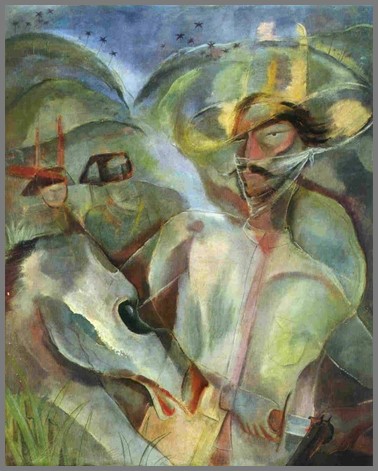

Modern Cuban Art

In the late 1920s, a group of young artists in Havana began to paint using non-traditional styles appropriated from European modern art. They were reacting against the various forms of naturalism promoted by Cuba’s art academy, San Alejandro, and seeking to renovate or even revolutionize Cuban art. The new direction(s) in art were then called: arte nuevo, vanguardia, and moderno. Today, it is mostly known as modern. The new tendency triumphed by the mid 1930s and thrived in the 1940s and 1950s. Since then, Cuban art is discussed in terms of generations, rather than movements, and these coincide with decades. Among the best-known artists of the 1930s, also known as the vanguardia generation, are Eduardo Abela, Víctor Manuel García, Amelia Peláez, Antonio Gattorno, Fidelio Ponce de León, Arístides Fernández, Carlos Enríquez and Wifredo Lam. They tended to simplify forms and painted in more saturated colors than traditional art. These artists also reinvigorated certain “Cuban” themes, like the island’s landscape, peasants and their traditions, and AfroCuban culture, with sympathy for the working poor and the marginalized.

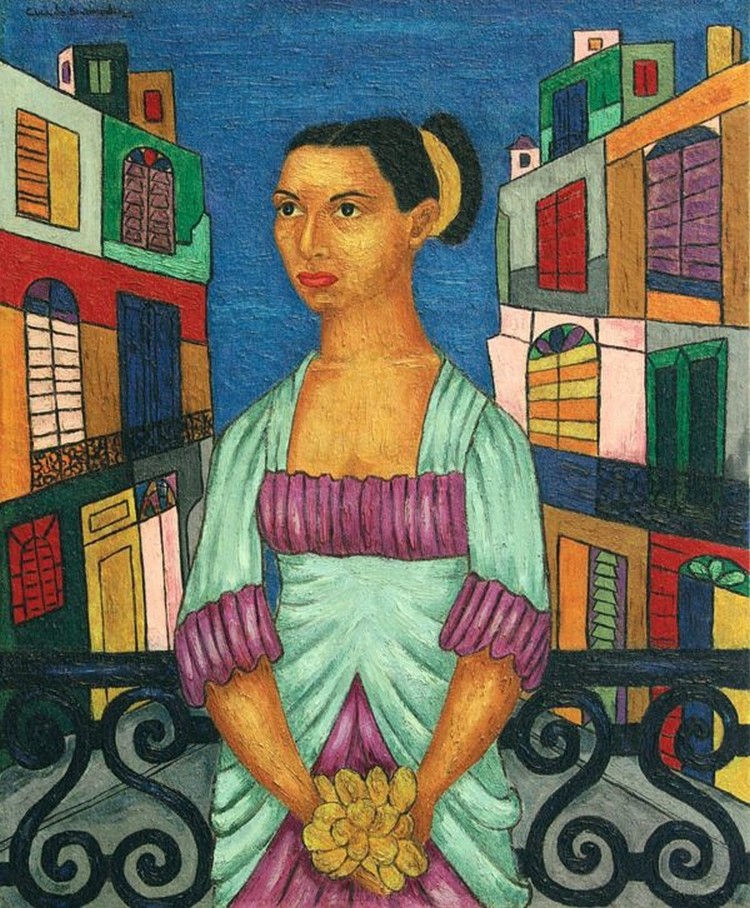

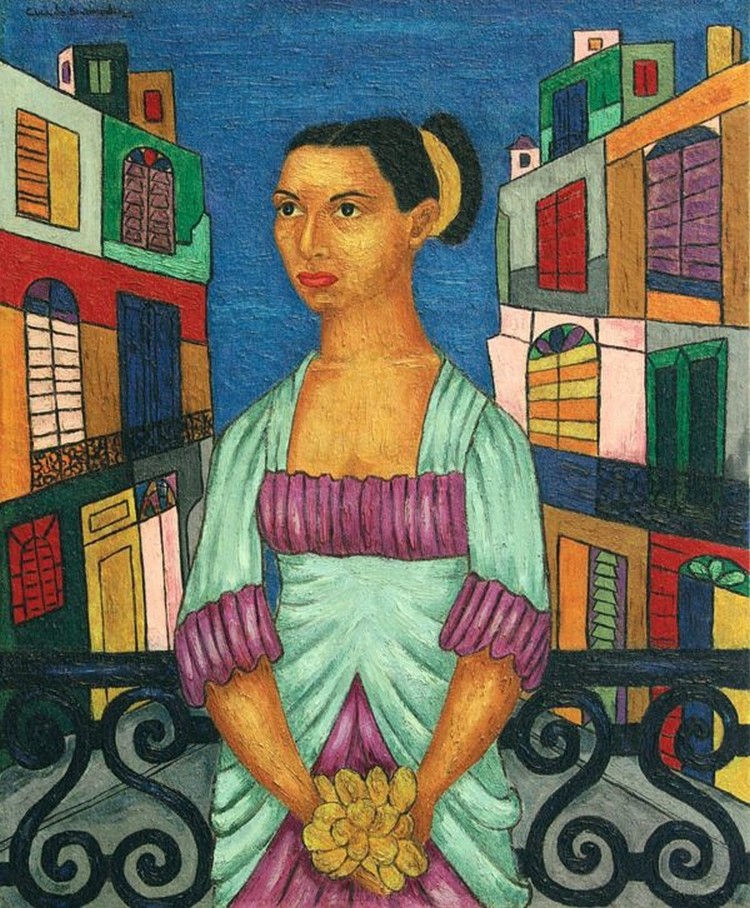

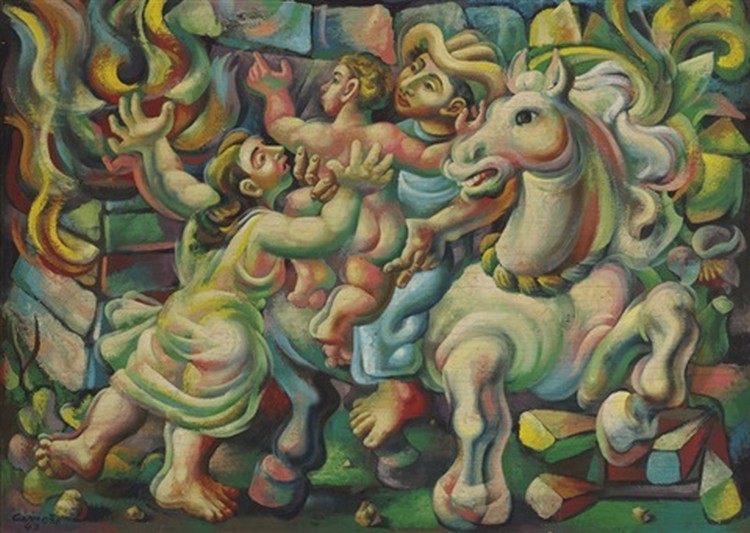

The 1940s generation introduced bright coloration and elaborate forms, often labeled as neo-baroque. This approach to form, thought at the time to have a certain Cuban quality (compared to then Mexican or North American art), was used to represent quotidian life with emphasis on the city of Havana. The outstanding artists of that generation are Mario Carreño, René Portocarrero, Mariano Rodríguez, Cundo Bermúdez, Roberto Diago, Mirta Cerra, and Luis Martínez Pedro. To be sure, the art of Peláez and Lam reached their full force in the 1940s.

A new generation of artists emerged in the 1950s, some continued to work with figuration and the most avant-garde turned to abstraction, influenced by such a tendency in global modern art at mid-century. Among the better known artists of that generation are Agustín Cárdenas, Guido Llinás, Hugo Consuegra, Raúl Martínez, Tomás Oliva, Raúl Milián, Rafael Soriano, José María Mijares, Agustín Fernández, Loló Soldevilla, and Sandú Darie. In the 1960s, painting was challenged by film, photography, and posters, art forms with potential to reach the masses as desired by the revolutionary government. Three major painters emerged during that decade, Antonia Eiriz, Angel Acosta León, and Servando Cabrera Moreno, while Martínez transformed his style from abstract expressionism to an adaptation of pop art.

The artworks of the fore mentioned artists and a few others are the ones that make up the collections discussed in this essay. Modern Cuban art was for decades collected by a Cuban educated elite, mostly professionals, and a few foreigners. The artworks, mostly paintings, were sold for moderate prices, or even gifted to friends. Beginning in the 1990s, the art of the first and second generation began to be assiduously collected outside of Cuba, mostly in this country, and the prices increased considerably. After years of neglect by curators and collectors, the works of the third generation are increasingly exhibited and collected.

The Collectors

I have known twenty some collectors of modern Cuban art in Miami since the 1980s. Their collections have ranged from about twenty to fifty or more paintings, less so drawings, and even less sculpture. In two cases, the collections have over one hundred pieces. The collectors have been primarily businessmen, doctors, and lawyers. They are mostly men or couples and in two cases women. Their ages range from the forties to the eighties, and in some cases those I will mention have passed away. The older ones were familiar with Cuban art before exile and the younger ones became aware of it in Miami. The ones I have known are part of a Cuban elite, who migrated to this country in the 1960s, are well educated, come from solid middle-class to prosperous families, and have succeeded in business or the medical and law fields. They consider themselves Cuban, rather than Cuban American, and their self-image as exiles or immigrant is in flux.

Some Collecting Issues

The collecting issues of motivation, privacy, length of collections, and forgery are not unique to Cuban art. However, these matters have some characteristics that are unique to its collection in Miami.

In an article on collecting art in Britain, Zaza Hlalethwa, succinctly states the basic motivations for collecting art practically everywhere. “Centuries ago, a lucrative culture of buying art was established. Rich people began buying art for three reasons: it looks beautiful, it makes money while it rests in their homes, and buying art is something that other rich people do.” (The History of Collecting Art-a Timeline, The Guardian, London, June 1, 2018). Thus, aesthetics, investment, and status drive this old and nearly universal practice.

These three motivations are present in our case, but each incentive has played changing roles since the 1930s. Up to the 1980s, aesthetic and cultural values were probably the dominant motivator in collecting modern Cuban art. In more recent times, investment has become more prominent. The global economic tendency to see art as a highly desired commodity coincided with the demand and increasing prices for modern Cuban art in the last thirty years. These circumstances have led to the emphasis in the economic incentive. At the same time, the increase in prices has left out the intellectual middle class that originally collected the art in question. The issue of status has been constant in the collecting of Cuban modern art. For the intellectual class of its day, among which it circulated, the art provided the status of being progressive and cultured. It separated them from Cuban society’s old and new money class, specially the philistines among them. In more recent times, the sought status is also socio-economic.

Beyond the outlined motivations, there are other important ones in our case. For Cuban and Cuban Americans (those born or raised in this country), a major desire for collecting has been pride in their Cuban identity and an affirmation of it on their walls. The condition of prolonged exile, existing side by side with permanent migration, and until recently the impossibility of even visits to the homeland, left Cubans without direct contact with much of their material cultural heritage. Works of art have provided a tangible and symbolic approximation to their culture. This has been particularly so in the case of pre-revolutionary works of art, those from the time that nurtures Miami’s Cuban nostalgia.

Yet, there is more to collecting. Zara Ellis, in her brief study, Gustave Caillebotte as a Collector of Impressionist Painting, gives a more nuance view of art collecting. “He bought many spurs including fulfillment, curiosity, respect and social acceptance. Collecting to Caillebotte was exciting, tempting, and adventurous. It brought him satisfaction but, it also brought him responsibility to preserve and protect." (Gustave Caillebotte and hisRelationship to his Contemporary Art Market, Cheshire, Book Treasury, 2013). These motivations and behavior are present to different degrees in the collectors I have known. Motivations for collecting art are numerous and overlap. Temptation, excitement, personal satisfaction, and the responsibility to preserve live side by side. The preservation of modern Cuban art in Miami after decades of being exposed to all kinds of conditions, like excessive heat, humidity, and in some cases neglect, needs better acknowledgment.

One of the issues that at first surprised me was the desire for privacy. I have repeatedly run into collectors of Cuban art who did not want to be identified by name or at least want to keep certain purchases a secret. This was particularly the case in the 1980s. Some did not want to call attention to themselves and their valuable possessions. Most were fearful that the original owners, whose art was taken by the government upon their departure for exile or was left with relatives or friends when they left Cuba and then sold, would reclaim them. Particularly In the 1990s, during Cuba’s economic depression, government, relatives and friends sold the art in their possession to survive. A lot of it ended in Miami and claims were made. In a few cases, the collector just wanted to be left alone. The interest in privacy is perhaps best seen in the Lists of Works section of the exhibition catalogues of the Museo Cubano de Arte y Cultura (Miami), where many collections are labeled Private Collections. Today, most collectors list their names.

The historical record teaches us that private collections of art are usually in flux, individual works or entire collections come and go. This is particularly the case In Miami with the art in question. The majority of the large collections of modern Cuban art have lasted about one decade, a few were in place for twenty years, fewer longer than that. Business bust, divorces, older age and death, or just loss of interest has resulted in selling the artworks. Except in two cases, the collections discussed in this essay no longer exist or are being dismantled as I write. I include them because they should be part of the historical record. They have played an important role in the exhibition, preservation, and study of modern Cuban art. Small collections tend to be more stable.

The one problematic issue has been forgeries. Whenever the art market goes up in relation to an artist, movement or country, there is the appearance and surge in forgeries. In the case of modern Cuban art, it is a post 1990 phenomenon. Growing wealth among Cubans in Miami since the 1980s, coupled with the Cuban economic depression of the 1990s, increased the demand and accessibility to modern Cuban art. This in turn resulted in raised prices and an opportunity to make easy money from fakes. The lack of experts outside of Cuba made the situation worse. Forgeries were made in Cuba, Mexico, Spain, Miami, among other places. These forgeries complicated the situation, but did not diminish the demand. Consequently, many collectors bought fakes at one point or another, eventually finding out the truth. It did not help that some individuals, who were familiar with modern Cuban art, but were far from being connoisseurs, declared themselves experts and began to give certificates of authenticity.

Matters were complicated by at least two factors. One was the peculiar method of doing authentications in the 1990s. The persons seeking a certificate would only pay for the service if the expert deemed that the work was real. Thus, the system encouraged erring on the side of authentic. Secondly, many times authentications were asked after the piece was bought. This was equally problematic. My observation does not excuse any lack of ethics on the part of the so-called experts. They and I should have done a better job at educating collectors to the fact that a “no” is more valuable than a “yes,” for it saved money and face. I did reports of authenticity for works of art by Enríquez. I began when I was doing research for a monograph on this artist and wanted to see as much of his art as possible. By that time, I had seen a large sampling of his work in Havana and Miami. I detected many fakes and made mistakes both way. A few that I thought were good turned out to be false and at least two that I thought at the beginning to be false were authentic. Visually, the range of fakes goes from obvious to convincing.

For anecdotal sake, these are some of the situations I encountered with fake paintings. Many were done on old canvas, erasing the previous painting, and often using the old frames, nails, backboards, and even dust. Signatures were erased and replaced by desired ones, often above the original. Paintings were urinated on and put in an oven to create a worn surface. A kind of instant aging. Marine transparent sealing was put on the painting to make it oblivious to black light. Many false and hard to prove provenances made this useful tool useless. Fake certificates of authenticity also abound. One ingenious trick was to use difficult to find catalogues and books, replace the original illustration on a given page with the photo of a fake, make a xerox, and present it to the potential buyer. The list goes on.

Arrival and Circulation

Where did these artworks come from and how did they get here? Some of it arrived in Miami with the first Cuban refugees in the 1960s. A lot more was brought to this country in the 1940s and 1950s by art dealers or collectors visiting Cuba. The vast amount arrived from everywhere post 1990.

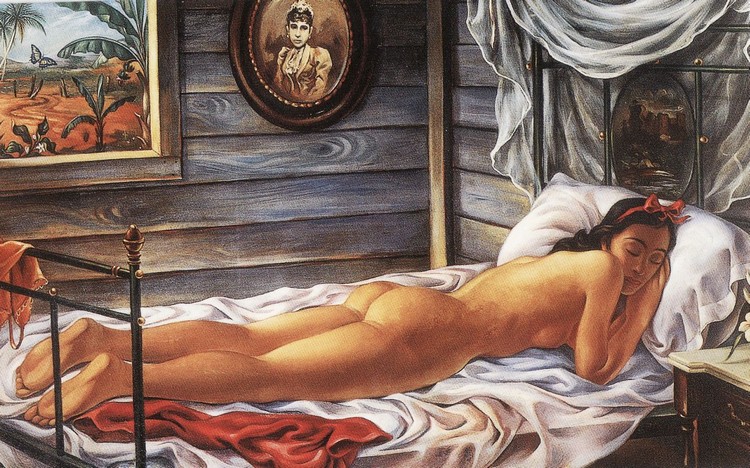

Some lucky Cuban exiles who left early after the revolution were able to bring at least part of their collection. Others were able to smuggle their collection with the help of foreign embassies. One salient example is that of Isabetta Lancella, the daughter of Enríquez and Alice Neel. In the early sixties, she returned to her father’s house/studio in the outskirts of Havana, known as the Hurón Azul, and recuperated about a dozen paintings and drawings. She then took them out of Cuba with the help of someone in the Spanish embassy. These included two major pieces of the 1930s: Hamlet c. 1933 and Musicos 1935. All of the works ended up in Miami and are still mostly in the collection of Isabetta’s family. Some exiles brought just a few pieces without much drama. As the Cuban exodus began in earnest in the early 1960s, the government only allowed persons leaving the country to take a few articles of clothing and a ridiculous amount of money.

The art historian, curator, and director of the Art Museum of the Organization of American States, José Gómez Sicre, organized a number of shows of the art in question and had them travel throughout the U.S. during the 1940s and 1950s. The art in those exhibitions was for sale. Later, the art dealer Ramón Osuna, also based in Washington DC, sold Cuban art from his galleries, the first named Pyramids Gallery, then Osuna Art Gallery. They are important pioneers in the marketing of Cuban art in the United States. At mid-century, a number of New York art galleries represented Cuban modern artists: Pierre Matisse (Lam), Perls (Carreño), Julian Levy (Portocarrero), Rigl (Mariano), and Delphic Studio (Ponce). It should also be noted that American tourists, upon recommendations from Gómez Sicre and others, visited artists and bought Cuban art in Havana. Beginning in the 1980s and picking up the pace after 2000, many of the artworks bought in Cuba or sold in this country in the 1940s and 1950s arrived in Miami. Most famously, about a third of the paintings shown in the storied 1944 exhibition Modern Cuban Art at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, are today in Miami private collections. In the majority of cases, the artworks that came to this country at mid-century disappeared from view. Two telling cases are Enríquez’s Las Tetas de Madruga 1943 and Gattorno's La siesta c. 1940

and Gattorno's La siesta c. 1940 .

These were well-documented paintings when first shown, then disappeared from view, their whereabouts unknown. The first painting was found, by the collector and gallery owner Ramón Cernuda, in a private collection in Dallas, Texas in 2005; the latter was found by the writer Sean Poole in an attic in Massachusetts towards the end of the 1990s.

.

These were well-documented paintings when first shown, then disappeared from view, their whereabouts unknown. The first painting was found, by the collector and gallery owner Ramón Cernuda, in a private collection in Dallas, Texas in 2005; the latter was found by the writer Sean Poole in an attic in Massachusetts towards the end of the 1990s.

Beginning in the 1980s, Christie’s and Sotheby’s auction houses began to have specialized sales of Latin American art. These soon began to be important supply sources for modern Cuban art bought by Miami collectors. The art sold by these auction houses comes from all over the world and in the case of Cuban art, a representative amount was bought by North Americans going back to the 1940s. The most famous example is Alfred Hitchcock acquisition of Ponce's Five Women after the MoMA show, resold by Sotheby’s in 1991. Another significant case is the 1984 Sotheby’s sale of Joseph Cantor’s collection of fifteen oils and eleven works on paper by modern Cuban artists. Mr. Cantor was an Indianapolis collector, who made his money in motion picture theaters and real estate. He began buying paintings by Lam during his first trip to Havana in 1949. Among the paintings in the sale were Lam’s renown Cuatro Elementos 1945, and Antilles Parade 1945. He also owned a few Portocarrero’s, including Figuras de carnaval 1952, and Ponce’s large Florero c. 1943. In the 1940s, Ponce introduced color into his paintings, the touches of pink and green in this still life attest to that new direction in his art. All of these major paintings are in Miami today. The selling of important paintings long in North American collections, but away from the public eye, continuous to our day. One major example is the 2007 sale in Sotheby’s of Carreño’s La danza afrocubana 1943, one of three related large duco paintings about life in the Cuban countryside. It was exhibited in Havana’s Lyceum in 1943 and in the 1944 MoMA exhibition, then Perls Art Gallery, which represented Carreño, sold it and it remained in a private collection for fifty years. The painting was bought by Cernuda Arte for a record 2.6 million dollars and ended in a Miami collection.

after the MoMA show, resold by Sotheby’s in 1991. Another significant case is the 1984 Sotheby’s sale of Joseph Cantor’s collection of fifteen oils and eleven works on paper by modern Cuban artists. Mr. Cantor was an Indianapolis collector, who made his money in motion picture theaters and real estate. He began buying paintings by Lam during his first trip to Havana in 1949. Among the paintings in the sale were Lam’s renown Cuatro Elementos 1945, and Antilles Parade 1945. He also owned a few Portocarrero’s, including Figuras de carnaval 1952, and Ponce’s large Florero c. 1943. In the 1940s, Ponce introduced color into his paintings, the touches of pink and green in this still life attest to that new direction in his art. All of these major paintings are in Miami today. The selling of important paintings long in North American collections, but away from the public eye, continuous to our day. One major example is the 2007 sale in Sotheby’s of Carreño’s La danza afrocubana 1943, one of three related large duco paintings about life in the Cuban countryside. It was exhibited in Havana’s Lyceum in 1943 and in the 1944 MoMA exhibition, then Perls Art Gallery, which represented Carreño, sold it and it remained in a private collection for fifty years. The painting was bought by Cernuda Arte for a record 2.6 million dollars and ended in a Miami collection.

Two individuals working in Sotheby’s in the 1980s acted as an important conduit to Miami collections, Dolores Smithies and Giulio V. Blanc. They had extensive knowledge of Cuban art and were collectors themselves.

Whereas for decades modern Cuban art trickled to Miami, in the 1990s a flood gate opened. Miami art galleries, independent dealers, and major auction houses provided a growing prosperous class of Cubans a steady supply of art. A significant part of that supply came from Cuba. The necessities brought about by the economic depression of the 1990s, known as the Periodo Especial, led the Cuban government to allow the sale and exportation of the art in question. The dire poverty there and the wealth here also led to a good amount of smuggling. This was particularly the case with those artworks considered by Cuban officials to be too important to leave the country and classified as National Patrimony. Some of the work coming from Cuba belonged to known prime collections, others came from the professional class at large.

After my book on modern Cuban art came out in 1994, established and improvised dealers began to contact me in order to show me works of art recently brought from Cuba. Sometimes they knocked on the door of my former West Miami home without calling first. They obtained my phone and address from acquaintances of acquaintances. During a period of about two years, many came looking for certificates of authenticity and names of potential buyers. I provided only questions and my gratis oral opinion on the pieces. I saw many paintings ranging from fakes to pieces deemed national patrimony. Three stand out in my memory. One day a person just showed up and laid on the floor of my living room Enríquez’s Horno de carbon 1937, looking badly damaged from the smuggling operation. This is one of the earliest and foremost Cuban protest paintings, based on an actual event the artist witnessed in a trip to the interior of the island. The image shows two malnutrition men tending to a primitive coal oven in a hellish landscape. When I first saw it, my heart began racing because of the importance of the piece and the fact that it was almost destroyed. On another occasion, I was shown Enríquez’s Diablito 1938. The relatively large painting shows an elaborately costumed shaman dancing in presumably an Afro-Cuban religious ceremony. This painting had been out of sight for decades and was remembered from a photograph in a journal and an exhibition entry. In this case, it was in rather good conditions. The third of the outstanding pieces brought to me was Ponce’s Naturaleza muerta con jarron chino, c.1944. This is a large, colorful and ambitious still life, well documented and liked in its day. These paintings stayed in Miami and are in practically the same private collections since they arrived.

Local gallery owners and dealers working out of their houses are responsible for obtaining and selling the bulk of the modern Cuban art in this city. Among them, Cernuda of Cernuda Arte has been instrumental in finding long forgotten and more recently acquired modern Cuban art. His many findings can be seen in his yearly publication, Important Cuban Artworks. The following are some of Mr. Cernuda’s most significant acquisitions for his gallery.

Carlos Girón Cerna was a poet and Guatemala’s General Counsel to Cuba in the 1930s. He and his wife Rosie befriended the Havana intellectual and artistic vanguard of the time. He became close with Ponce and acquired some outstanding and rare pieces from the artist, such as El baño 1935, showing two nude bathers coming out of a body of water, and Naturaleza muerta 1935, a minimal image full of pathos, rather than the expected sensuality associated with such a genre in Cuban art. In the collection were also two notable portraits of Rosie, one by Victor Manuel and one by Ponce, which accentuate their very different styles.

In the following decade the European writer Robert Altman took refuge in Cuba from World War II. He befriended many Cuban artists and intellectuals of the time, married a Cuban woman named Hortensia, and among other things wrote and lecture on art. He put together a premier collection of modern Cuban art, which he took to New York in the 1950s and later to Paris. Recently he has parted with part of his collection and some of it ended in local collections through Cernuda Arte.

Other foreigners, who lived and bought modern Cuban art in Havana in later decades, were William Bowdler and Madame Odette Lavergne. Bowdler was a political officer in the United States embassy in Havana, 1957 to 1961, and bought paintings by Víctor Manuel, Portocarrero, Bermúdez, Estopiñán, and Milán; Lavergne lived in Cuba between 1964 and 1971, as wife of the Canadian ambassador, amazing a collection of fifty eight pieces. She had a preference for Víctor Manuel, Peláez, and Portocarrero. Many of them are today in Miami collections.

Among the better known Cubans whose collections Mr. Cernuda acquired, all or in part, are that of the husband and wife poets Cintio Vitier and Fina García Marruz and that of Carmen Armenteros. Both were strong in paintings by Ponce.

Some of the collections brought to Miami by Mr. Cernuda were put together outside of Cuba. One unexpected place was Haiti. Gómez Sicre organized a number of exhibitions of modern Cuban painters in Port-au-Prince in the 1940s at the Centre D’ Art. This center was led by the North American Dewitt Peters and apparently became a place where some of the Haitian elite and foreigners working in Port-au-Prince bought Cuban art. Dr. Gerard Lescot, the Minister of Haitian Foreign Affairs between 1941-46, bought a group of fine Enríquez’s paintings and drawings. He also commissioned the artist when visiting Haiti to do a portrait of his wife. His most important acquisition was Enriquez’s Heroe criollo 1941-2. In the early 1940s, Enríquez painted two similar oils of a mounted desperado with a woman in his arms and a gun in his hand, running from an unseen threat. These are two outstanding paintings by this artist. He titled one Bandido criollo 1943, which he sent to the New York MoMA exhibition of 1944, and the other, Heroe criollo, which he sent to an exhibition in Mexico and then to Port-au-Prince. Heroe criollo was never heard from again and it was thought that both titles belonged to the painting that went to New York. It is not unheard of that a work of art goes by two names over time. Then in 2009, Heroe criollo was reunited with Bandolero criollo on the walls of Cernuda Arte and their history clarified.

In the early 1940s, Enríquez painted two similar oils of a mounted desperado with a woman in his arms and a gun in his hand, running from an unseen threat. These are two outstanding paintings by this artist. He titled one Bandido criollo 1943, which he sent to the New York MoMA exhibition of 1944, and the other, Heroe criollo, which he sent to an exhibition in Mexico and then to Port-au-Prince. Heroe criollo was never heard from again and it was thought that both titles belonged to the painting that went to New York. It is not unheard of that a work of art goes by two names over time. Then in 2009, Heroe criollo was reunited with Bandolero criollo on the walls of Cernuda Arte and their history clarified.

Perhaps the first collection of modern Cuban art belonging to a North American happened in Port-au-Prince. Maurice De Young III, while manager of Hotel Olaffson in the mid-1940s, befriended Mr. Peters and amassed a collection of modern Cuban art. He bought multiple paintings by Bermúdez, Enríquez, Mariano, Martínez Pedro, and Víctor Manuel. Upon his return to the United States, he brought his collection with him and recently his family sold it. Many of these works are today in local collections.

Other gallery owners have also played important roles in this story. Roberto Borlenghi, the owner of Pan American Art Projects, has a sharp eye honed from many years of working with art and the experience of two decades of purchasing visits to Cuba. Although he mainly represents contemporary artists, Mr. Borlenghi has brought large quantities of modern art out of Cuba, most notably pieces which border on national patrimony. To mention a few: Víctor Manuel’s Olvidados 1940s, a large and rare painting about ill fated Jewish refuges from WWII; Mariano's Mujeres luchando c.1940,  one of his first colorful, sensual paintings; Diago's Pianista 1940s,

one of his first colorful, sensual paintings; Diago's Pianista 1940s,  an over five feet oil on paper on canvas of an Afro-Cuban entertainer; and Peláez Peces grises 1931, a large, unusually dark, rather abstract, and stunning still life from her Parisian period.

an over five feet oil on paper on canvas of an Afro-Cuban entertainer; and Peláez Peces grises 1931, a large, unusually dark, rather abstract, and stunning still life from her Parisian period.

Mr. Borlenghi bought the Diago from Antonio Alejo, a professor at the San Alejandro academy, who apparently got it from the artist. Pianista was part of a diptych, which other side did not survived due to irreparable damages. He bought Pescado gris from the son of a Havana collector named Luis Blanco, who acquired it from Peláez. Porfirio Sardiñas was a one-artist collector, he befriended and bought only works by Victor Manuel. Roberto bought his collection, including Olvidados. Jorge Fernández de Castro and his wife Marta Sardiñas, Porfirio’s sister, put together a limited, but exquisite collection of paintings by Enríquez, Víctor Manuel, Ponce, Peláez, Portocarrero, Mariano, Bermúdez, among others. Jorge was a lawyer, who came from a well-known family in Havana, and along with his wife had close ties with most of the Cuban modern artists. Long after Jorge’s death, around 2000, Marta took her collection surreptitiously to Spain. Soon thereafter, Mr. Borlenghi acquired most of it, including the much reproduced Bermúdez’s Retrato de Marta 1940s  and Enríquez’s L’Écuyère c. 1933, He also bought Enríquez salacious drawings for the illustrations of a controversial and erotic poem by the Renaissance author Pietro de Arentino.

and Enríquez’s L’Écuyère c. 1933, He also bought Enríquez salacious drawings for the illustrations of a controversial and erotic poem by the Renaissance author Pietro de Arentino.

Recently, Mr. Borlenghi exhibited in his gallery about eighty modernist works dating from the 1920s to circa 1960. In the group were significant paintings by Víctor Manuel, Peláez, Abela, Ponce, Enríquez, Bermúdez, Diago, Lam, Mariano, and Milián, among others. The exhibition also included two sculptures, one from Cardenas and the other, a large bronze, from Juan José Sicre. The latter was a pioneer of modern sculpture in Cuba and is rarely collected in the United Sates.

More notable galleries, which have sold modern Cuban art in Miami for years, are Gary Nader’s Nader Fine Art and Israel Moleiro’s Latin Art Core. The former offers modern art from Latin America, including Cuba, while the latter sells mostly modern and contemporary Cuban art. Latin Art Core has been at the forefront of marketing geometric abstraction from the 1950s and early 1960s. One other gallery, Tresart, founded by Antonio de la Guardia in 2006, specializes in modern and contemporary Cuban art. He has also been successful in importing modern paintings from long standing Havana private collections.

There is a relatively new development in the demand for modern Cuban art. Speaking to two gallery owners recently, I was told that they are increasingly selling the art in question to collectors outside of Florida, many of them North Americans. Participation by Miami galleries in art fairs in Dallas, Los Angeles, Atlanta, New York, and Chicago have helped to expose modern Cuban art and widened the circle of collectors. For instance, Bermúdez's famed Romeo y Julieta 1943 , was in two Miami collections since at least the early 1980s. Recently, Mr. Cernuda sold it for about half a million dollars to a collector in Massachusetts. Christie’s and Sotheby’s semiannual auctions of Latin American Art are also exposing the art in question to collectors everywhere. The continued curiosity about Cuba among North Americans and Europeans feeds those markets.

, was in two Miami collections since at least the early 1980s. Recently, Mr. Cernuda sold it for about half a million dollars to a collector in Massachusetts. Christie’s and Sotheby’s semiannual auctions of Latin American Art are also exposing the art in question to collectors everywhere. The continued curiosity about Cuba among North Americans and Europeans feeds those markets.

Collections

The first major collection of modern Cuban art that I saw belonged to José Martínez Cañas. He was president of Frito-Lay of Puerto Rico from 1972 to 1977, when he put the collection together. In 1980, his collection was exhibited at the former Metropolitan Museum of Art of Miami, located at the time in the historic Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables. The museum occupied the second floor of the loggia behind and to the right of the hotel. A courtyard with a fountain and two grand staircases welcomed the viewer. It was actually a collection of modern Latin American art, which included many Cuban artists. There were fifty paintings in total. The Cuban selection was first rate and included works by Ponce, Peláez, Enríquez, Carreño, and Portocarrero, among others. It had five excellent Peláez paintings, three from her European stay, Mujer sentada 1929, Crisantemus 1930, and El coco 1932, one from the height of her career, a still life from 1943, and another still life from the 1954. He also owned one of Lam’s best-known renditions of the woman horse theme, Femme Cheval 1950 .

.

Two paintings stopped me on my track that day. These were Enríquez’s Eva c. 1940 and Ponce’s San Ignacio de Loyola c. 1938-39 . Eva is a medium size canvas of a nude with a dreamy facial expression and painted in transparent layers of blue and green tonalities. The guard, seeing me stand in front of it for a while, came over and told me: “she was the painter’s second wife and when she left him for a woman, he put a knife through the figure’s stomach. Look closely and you will see where it was restored” I thought, what a painting and what a story! I told myself, I have to find out more about this artist. In 2010, I published a monograph on him, Carlos Enríquez, The Painter of Cuban Ballads. In the case of Ponce, I was moved by the extensive use of white, the strange still life of a rabbit with a dagger stuck on his bleeding neck, and the tilting figures. This painting, I mused, must be the most unique and the only irreverent representation of the founder of the Jesuit Order. I was also moved to research Ponce’s life and work, the result is an unpublished monograph, A Cuban Original: The Art of Fidelio Ponce de León. These two paintings were exhibited at the storied Modern Cuban Painters exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan in 1944. Sometime thereafter they ended up in Miami, where they are today.

. Eva is a medium size canvas of a nude with a dreamy facial expression and painted in transparent layers of blue and green tonalities. The guard, seeing me stand in front of it for a while, came over and told me: “she was the painter’s second wife and when she left him for a woman, he put a knife through the figure’s stomach. Look closely and you will see where it was restored” I thought, what a painting and what a story! I told myself, I have to find out more about this artist. In 2010, I published a monograph on him, Carlos Enríquez, The Painter of Cuban Ballads. In the case of Ponce, I was moved by the extensive use of white, the strange still life of a rabbit with a dagger stuck on his bleeding neck, and the tilting figures. This painting, I mused, must be the most unique and the only irreverent representation of the founder of the Jesuit Order. I was also moved to research Ponce’s life and work, the result is an unpublished monograph, A Cuban Original: The Art of Fidelio Ponce de León. These two paintings were exhibited at the storied Modern Cuban Painters exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan in 1944. Sometime thereafter they ended up in Miami, where they are today.

An aside. Certain art exhibitions in important museums place a stamp of approval on artists, movements, or schools of art and add value to the works of art shown in it. The aforementioned exhibition at MoMA, which Cuban art historians and collectors have elevated to the realm of the mythic, is one of those.

“Mr. Cañas's possessions were attached after he was sued over misappropriation of funds. Judgments rendered over several years in Pepsico's favor [the parent company of Frito-Lay] transferred ownership of the instruments, as well as that of 50 Latin American paintings, which sold for $578,800 at Sotheby's in May of 1984”. (New York Times, June 29, 1984) Today, one of the paintings in that collection will easily cost the amount of the entire collection then. In the late 1980s and beyond, I saw many of these paintings in local collections and exhibitions at the former Museo Cubano de Arte y Cultura.

My early interest in Cuban art led me to curate a twenty-seven paintings exhibition with the ambitious title Origins of Modern Cuban art. Its setting was the Frances Wolfson Art Gallery of Miami-Dade Community College, downtown campus, and the year was 1982. At the time, I was working in that college as an art historian and Sheldon Lurie, the curator of the gallery, encouraged me to do the show. It included major paintings from The Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Modern Art of the Organization of American States, Washington D.C., and the Museum of Arts of Daytona Beach. These were works that had never been exhibited in Miami. Through acquaintances of acquaintances, I contacted a small number of persons who collected modern Cuban art in Miami and whose paintings made up about half of the exhibition. Two of those collections are worth writing about.

One afternoon, I visited the home of the late Francisco Mestre, a businessman, who lived on Sunset Drive. We walked around a spacious living and dinning rooms, well lit from large windows, where he showed me about a dozen paintings. The two I chose for the exhibition were Enríquez’s Los mambises, 1940s, an energetic and painterly piece about Cuban freedom fighters in action during the War of Independence, and Peláez Los botes, 1929, an austere early cubist landscape done in Europe. The most impressive work I saw that afternoon had nothing to do with Cuba. In the backyard of the house, there was a large metal sculpture of a lion, supposedly from the Hellenistic period.

During the local search for my exhibition, I came upon one of the best collections of modern Cuban art of any time and place. Lodovico and Conchita Blanc, with the help of their art historian son, Giulio, put together an exquisite collection of mostly masterpieces. They welcome me into their Coconut Grove home, which different from Mestre’s, its spaces were relatively small and dark. In an unassuming way, Lodovico show me one magnificent painting after another.